ARCHITECTURES HABITABLE AND NON-HABITABLE

ARCHITECTURES HABITABLE AND NON-HABITABLE

We too, like the national Nanni, the thing we like most is to see the houses

APRIL 2024 - GAZE

"The thing I like most of all is seeing the houses. Even when I go to other cities, the only thing I like to do is look at the houses. It would be nice to have a film made only of houses: panoramas of houses."

Nanni Moretti

These words are spoken by Nanni Moretti of Caro diario, the director’s rather faithful alter ego, who entrusts this film with some of its most ineffable oddities.

That it is in fact an oddity, this Morettian love for houses, is a certainty that suddenly strikes those who, like the writer, have always associated the love for bricks with the bourgeoisie and, consequently, with certain slightly conservative right-wingers – what is called the “reflective middle class”. That is, the one that, for example, Carlo Goldoni mocks in La casa nova (1760), a sarcastic comedy that takes aim precisely at the bourgeois passion for houses.

And yet, this passion – which is also thought to be a bit frivolous, as is often the case with fashion – has reaped illustrious and numerous victims, even in the highest spheres of the fatherland of letters. Let’s take, for example, a typical representative of the Italian intelligentsia, Mario Praz. Distinguished scholar, essayist expert of the Napoleonic period, writer, translator, journalist and fanatical collector of furniture, knick-knacks, paintings – especially the so-called conversation pieces depicting domestic interiors – as well as author of one of the inevitable texts in a self-respecting design bibliography, The Philosophy of Furniture (which was joined, in 1975, by the small jewel, now unfortunately out of print, The house of life).

In the book, Mario Praz even goes so far as to write – in black and white – what few intellectuals would confess: “As in any other field, so with furniture, men are divided into two classes: men who care about the house; men who don’t care at all. I feel much nearer to that wife of Zechariah of whom W. Hale White speaks in Revolution in Tanner’s Lane, who could not sit quietly if an ornament of the mantelpiece appeared to be displaced.”

And, if such a declaration were not enough to clear the field of any doubt about the dignity of studies around design and architecture, here comes the reinforcement of Felix Schwartz, a Swiss architect, with an assertion as lapidary as it is ontologically true: “Architecture is the clearest expression of the will, of the political intentions of humanity. By using architecture directly, man is directly influenced by it.” A statement impossible to deny, as demonstrated – fortunately only on paper – by Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon.

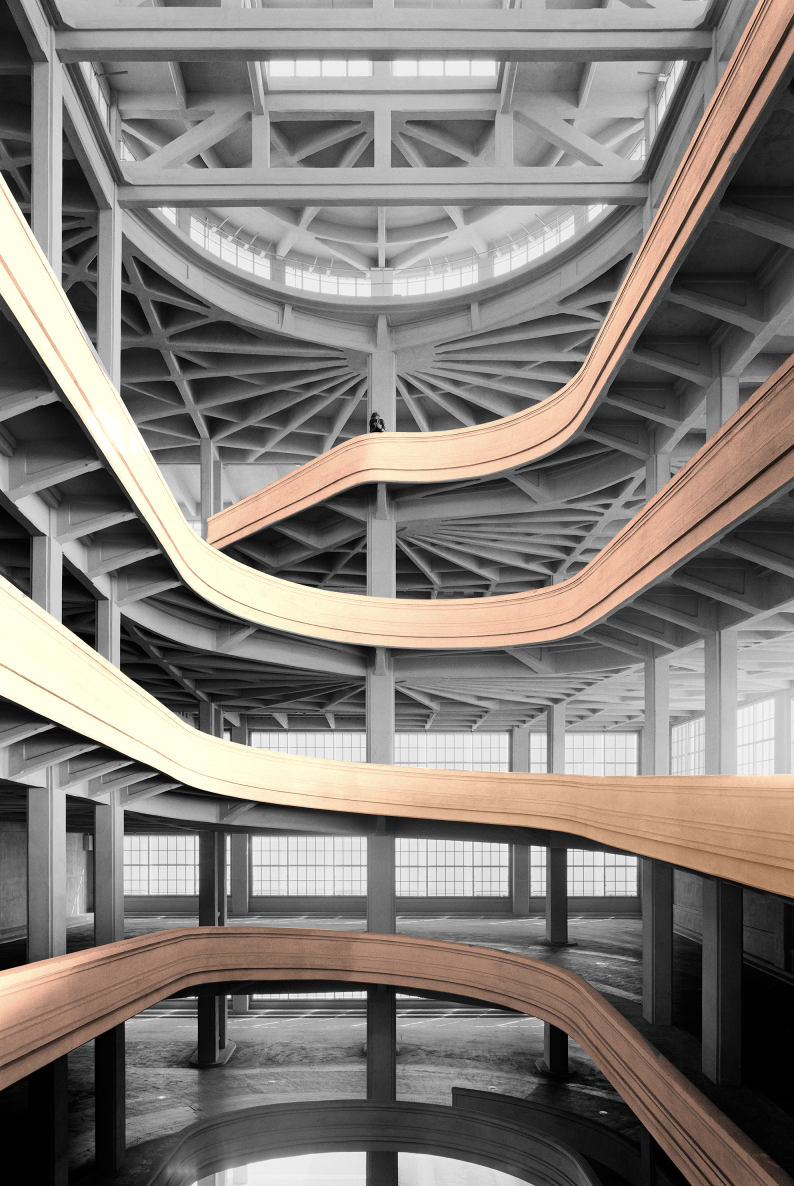

If, up to now, however, we have focused on talking about houses, places where we live, furnishings and furniture, what can we say instead of what – as Marco Belpoliti rightly notes in his speech in the catalogue of Uninhabitable Architectures (at the Centrale Montemartini in Rome until 5 May) – “has been built but is not intended to be inhabited”? Although they do not contemplate the dwelling dimension, in fact, the places chosen to trace the exhibition parabola of the Roman exhibition establish new forms of presence and interaction with man.

A perfect example, therefore, to represent the theme of form and function chosen for this issue. To clarify this for us, comes Andrea Canobbio’s The White Goddess, also from the catalogue published by Marsilio, a story about the Lingotto that writes of its own story: “I am the pure form, the perfect solid.” An immutable and even slightly obtuse pride, which contrasts with the rarefaction of the houses of Gibellina which, on the cold night of January 14, 1968 recounted by Stefania Auci in Stones and Silence, collapsed on themselves “returning to being stones, pieces of wood, nails”.

BY Enrica Murru

You may also read

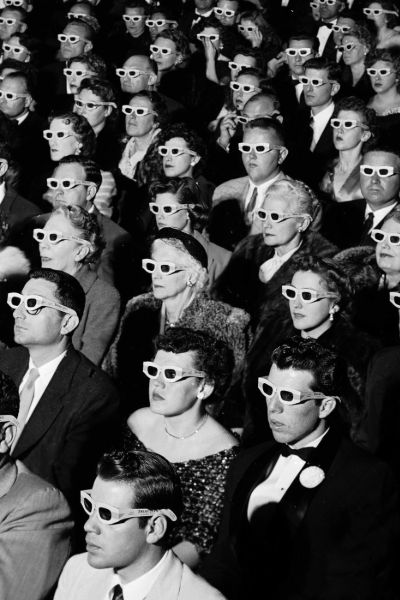

SAYING, DOING, KISSING, CINEMA, TESTAMENT

SAYING, DOING, KISSING, CINEMA, TESTAMENT Travelling between independent and arthouse cinemas, renov

The Christmas destinations where you can feel in the mood The Meraviglia

Le mete natalizie in cui sentirsi in mood The Meraviglia Biscotti allo zenzero, profumo di cannella,

HOME WEIRD HOME

HOME WEIRD HOME Extravagant architectural and urban planning episodes APRIL 2024 – GAZE Majara